Introduction

It’s currently about a week and a half before the start of my final exams as a fourth-year med student. As part of my revision schedule, I’m revising some ophthalmology content this afternoon – yes, even on CNY Day 1. Sad, right? Officially, we’re only granted a 1-week study break and this week just happens to be preceded by a weekend which constitutes the first two days of CNY 2024.

Specifically, here I am reading about age-related macular degeneration, and here’s an interesting sentence I chanced upon: “Other risk factors include smoking, gender, …, and hypermetropia”. As I read this the above sentence, I couldn’t help but ponder on the term ‘hypermetropia’. I was much more familiar with ‘hyperopia’, and wondered if they were truly synonymous. Alternatively, were there subtle differences that I’m not aware of?

Historical Perspective and Donders’ Influence

The journey begins with the work of Donders, a pioneer whose contributions in the 19th century shaped our understanding of refractive errors. Donders introduced the term ‘hypermetropia’ to describe a condition where the eye’s optical power is insufficient for its length, causing light to focus behind the retina. This term, etymologically derived from Greek—’hyper’ (over), ‘metron’ (measure), and ‘ops’ (eye)—captures the essence of the condition with remarkable precision: an eye that measures beyond normal.

Donders’ differentiation between hypermetropia and myopia, as well as his distinction from presbyopia, was a monumental step forward. It was a clarification that allowed for a more accurate diagnosis and understanding of visual impairments, distinguishing between the effects of aging and inherent optical power discrepancies.

The Etymological Critique by Duke-Elder

Sir Stewart Duke-Elder (after whom the Duke-Elder Undergraduate Prize is named), a towering figure in the field of ophthalmology, later critiqued the term ‘hyperopia,’ advocating for the original ‘hypermetropia’ as etymologically sound. His argument was rooted, I suppose, in the desire for terminological precision that fully encapsulated the condition’s nature. The term ‘hyperopia’—whilst shorter and arguably simpler—lacks the explicit reference to ‘measure’ that ‘hypermetropia’ carries. Duke-Elder’s concern was that ‘hyperopia’ might misleadingly suggest an elongation of the eye itself, rather than a discrepancy in its focusing capability.

Modern Usage and the Persistence of Both Terms

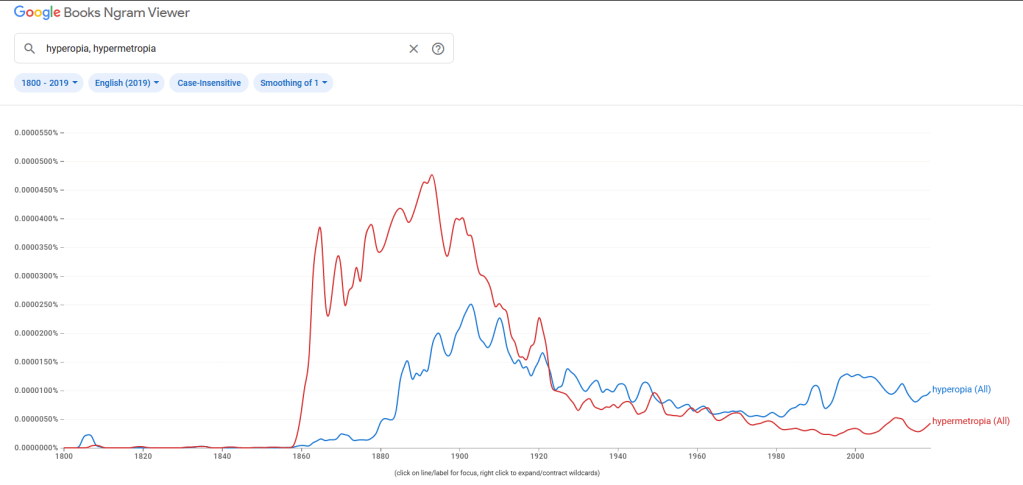

Despite Duke-Elder’s criticisms, it seems that both terms have persisted in the ophthalmic community, with ‘hyperopia’ seemingly being the more popular one (at least based on Google’s Ngram viewer (see below), which reports that ‘hyperopia’ has been consistently the more popular of the two terms since the 1970s). This could be because it’s a shorter word.

Embracing Linguistic Diversity in Ophthalmology

The debate between ‘hypermetropia’ and ‘hyperopia’ is a testament to the rich linguistic heritage of the medical profession. Staying true to etymology is how clinical tutors are able to teach medical students that ‘Staphylococcus’ looks like a bunch or cluster of grapes under the microscope, while ‘Streptococcus’ can be seen looking like chains. It underscores the importance of language in framing our understanding of medicine.

More broadly, I would say that from this example, we are reminded of the giants upon whose shoulders the field of ophthalmology stands. Donders’ legacy, enriched by Duke-Elder’s critiques, offers more than just a lesson in etymology; it invites us to appreciate the depth and precision that language brings to the science of vision.

Thus, let us cherish the diversity of its language, understanding that whether we choose ‘hypermetropia’ or ‘hyperopia’, our goal remains the same: to enhance the clarity of sight and understanding.

Let’s not be myopic about it 🙂

Leave a comment